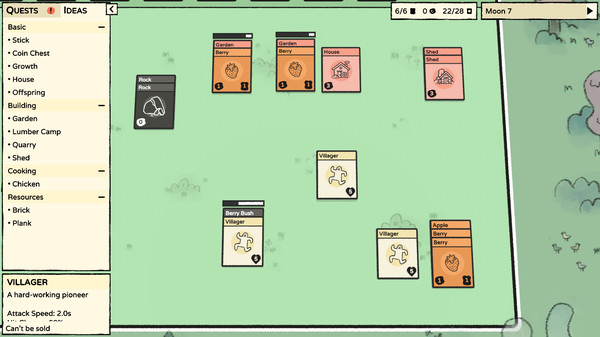

Stacklands blurs the line between card game and city builder ingeniously, constantly flipping between the two in my mind; One moment I’m placing wood onto my sawmill card to create planks like some wacky solitaire variation, the next I’m fully under the illusion I’ve created of a bustling village made up of warriors and wizards, brickyards and farms, only its all made of digital paper.

Stacklands starts simple, and while it progressively gets more and more chaotic, it never strays from that initial conceit: put a card on another card and something might happen. It’s like a real version of a game from a crap mobile ad – probably called Merge Monsters or something equally as generic – where the satisfaction comes from starting from a piece of wood and stone and somehow finishing the game with a smithy and blacksmith. In Stacklands, you manage resources like the aforementioned stone and wood, along with gold used to buy card packs, food used to feed your population, and your population to do population stuff.

The game is pretty hands off when it comes to progressing through its trials. There are no harsh winters that strain food supplies, no hostile neighbours threatening your town. The difficulty comes from how quickly you want to expand, naturally combining two humans with a house to create a baby. Each human needs a required amount of food per cycle, so as long as you can create enough food – be it through working forest cards to hunt for game or planting carrots on top of farm cards – the game will stagnate, which I should add, is a blessing. It is possible of course to lose at Stacklands, though given how easy it is to produce a robust food system, it’s not very likely.

Without the threat of failure, Stacklands could be considered a “cozy” game. Once I realised how unlikely it was I was going to see my quaint town crumble, I revelled in just admiring my villagers do their thing, harvesting basic resources, refining them into more valuable goods, exploring catacombs and the like. It’s worth noting that this admiration comes in large part due to how it’s almost all player created. Advanced automation is quite tricky in Stacklands, and doesn’t stretch further than cards of the same type stacking on top of each other without manual input. I adore how approachable Stacklands is, though by lacking any sort of depth in this sense, the game can become quite chaotic by the late game and pace wise slow down quite a bit. In the early stages of my village, I never used the pause function – whereby you can stop time and move cards around freely. By the time I had ten plus workers, smelters pumping out iron, and farms producing a frankly silly amount of carrots, I was having to pause the game every ten seconds to make sure everything ran smoothly, or rather, ran at all, given without player input, villagers won’t do anything, unless assigned to jobs like stone mining.

Though if you can push through the potentially overwhelming mid game, Stacklands never slows down in proving just how mindboggingly inventive it can be. New formulas and recipes are unlocked by those previously mentioned card packs, and each time I revealed a new one, I felt like I’d reached a new era in a game of Sid Meier’s Civilization, now wielding the power of agriculture, ore processing, fishing, animal husbandry, and weapon smithing. The list goes on, and each time I scored one of these groundbreaking recipes, I rethought how my village operated, how the new idea could would supplant my previous systems. Each card pack explores different niches, one focuses on food, another exploration, and another on combat. It was a joy gradually mastering each aspect of my village’s economy, nurturing a bountiful farmland, forging a profitable iron mine, and decking out my villagers with axes, magic wands, and frog hats. For the attack speed, of course.

It’s worth noting how all of this plays into the illusion of a city builder, because from screenshots or even video footage, Stacklands is blatantly a card game. Everything from humans to goblins to flint to onions, everything is a card, often with depicted with sokpop’s distinct cute and funny art style. Furthermore, when I talk about building these districts of my town, they’re little more than clumsy piles of cards. Sawmills are just a card labelled “sawmill” with a heaping ton of wood card plonked on top, slowly producing plank cards. My food industry was a particularly chaotic cacophony of carrot and campfire cards. And while this is totally and unavoidably messy – to a degree I thought was ultimately sensory overload and limited how much time I spent playing the game in the end – it’s utterly fascinating how my mind ended up filling in the blanks, where the black outlines of my ore deposits formed imaginary mountains of iron.

I never finished Stacklands I should note, because yes, I did find it a bit too overwhelming by the time my village was pumping out wood and iron at a pace any real economy would be envious of. Yet still, I walk away with the opinion Stacklands will at the very least entertain anyone, because while other games with a focus on city management often veer into complexity to replicate the real thing, Stacklands goes the other way, reducing what it takes to run a silly little village into the bare necessities, and wraps it up in a card based system anyone can engage with. It’s a profoundly innovative game from one of the most prolific developers out there.

Leave a comment